Never let the truth get in the way of a good yarn.

…so said the Australian philosopher cum outlaw, M. B. Read. In spite of his impressive track record of publication, Mr Read is (like I guess many philosophers) unheard of in academic circles. Though he steered clear of academia, a recent experience has me musing on the aptness of his quote as an idiom about that world. To me, his words capture the tension between the desire to demonstrate the falsifiability of our pet theories (‘the truth’), and the desire to go ahead and publish them anyway (‘a good yarn’).

In November 2017, the Association for Psychological Science published the special section on scholarly merit in psychological science; a collection of 22 articles from numerous academic authors. The findings are many, but if I might have a stab at the pith of their message: Success is the enemy of progress. That is, the quest for highest possible achievement and fame can erode our tenacity to learn and contribute to learning (Freund, 2017).

The story I am about to tell you might sound sardonic, in light of all that has been written in recent times about the fallibility of scholarly merit. However, I am writing in the spirit of optimism, hoping that readers (and that includes Honours students) are encouraged to think critically about research progress versus success. While I hope readers take something meaningful from what I say, it is not my intention at all to make anyone look bad. I do not name names, and any potentially identifiable information is replaced by generic terms in [brackets].

The objection

I recently marked a thesis about how early life experiences can have profound effects on development across the lifespan. The basic theory goes that trauma during childhood makes us prone to develop personality disorders (e.g. psychopathy) and engage in risky behaviours (e.g. armed robbery). Makes sense.

My overall assessment of the students’ work was favourable. I awarded the student a Distinction grade (75% to 84%). Independent of this, another marker assessed the work and arrived at a final score that was within five percent of mine. During the entire marking process, each marker was kept blind to the identity of the student, the student’s supervisor(s), and the other marker.

Later, I receive an email from an independent mediator, saying that the student’s supervisor has lodged an anonymous objection. The other marker and I were asked to read the objection, re-read our criticisms of the student’s work, then comment on whether the final mark we had agreed on seems fair enough. Can I get a “‘fraid so!”.

The unidentified supervisor rallied that my criticisms are “value judgements rather than fair critiques of the student’s work.” He also anonymously opined that “fundamentally, there is an equity issue here.” According to the supervisor, conceptually similar works by other students did not suffer the same line of questioning that I pursued in marking this particular work. Apparently, many of these have received High Distinction grades as well (85% or higher). So, you may be wondering, what did I say to prompt such an irascible plea?

Good correlational design

The supervisor’s objection boiled down to two comments I made on his or her student’s thesis. Here is the first:

I fear that simply reporting Pearson’s r as it relates to various pairs of variables is not a sophisticated or robust enough test of hypotheses.

In my experience, simple correlation is seldom enough to test hypotheses. Even if we ignore concerns about causation, you can infer almost anything by referring to a scatterplot.

Consider, for instance, the hypothesis that the redder a person’s hair, the angrier he is. Measure the level of red hue in each participant’s hair, and give participants a self-report questionnaire designed to measure anger. Hypothetically, the stereotype might be supported by a single correlation value or scatterplot. However, such output is meaningless in the absence of additional, relevant information – a measure of how frequently participants are teased about their hair colour might be a good thing to look at.

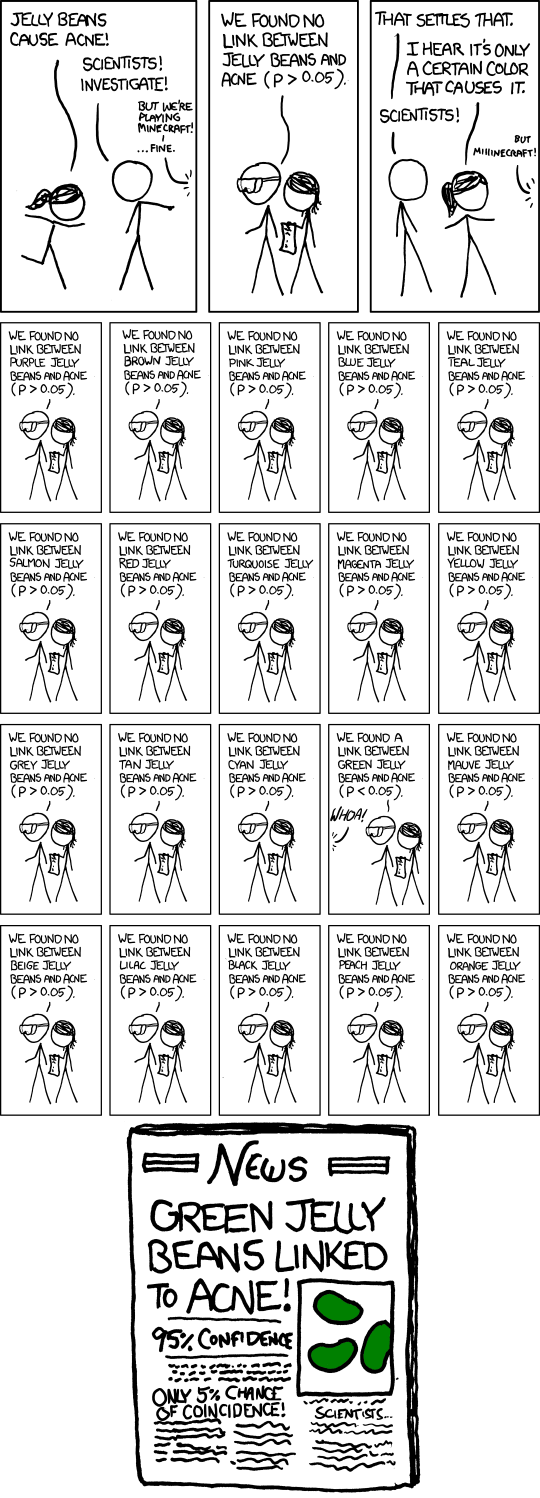

The thesis in question presented a table of 36 correlation values, followed by a few short paragraphs, to simultaneously infer outcomes from seven hypothesis tests – effect sizes and confidence intervals were not mentioned. Testing many hypothetical correlations in one go is not always reasonable without some sort of statistical intervention. In the thesis I marked, each correlation was deemed significant if it had less than a one in twenty chance of being ‘false-positive’ (p < .05; and this was never made explicit, but could be inferred from a footnote in one of the results tables). However, each of the 36 correlations were calculated from the same group of participants. This means that the overall likelihood of at least one false-positive result is more than the acceptable one in twenty. This comic by XKCD illustrates the exact problem I am getting at here:

Unfortunately, the thesis I marked had made no obvious attempt to correct for multiple tests, nor had it stated explicitly how many tests were run to evaluate the seven hypotheses (k = 36). Moreover, I did not read about any theoretically meaningful regression model – each of nine variables were simply correlated with each other in an exploratory manner (∴ k = T9-1 = 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 36). Thus, the student appears to be doing something that is liable to land him or her in the IVth level of scientific hell, which explains my first of two objected comments.

In conclusion, the best correlational designs are built on solid ground. The variables of interest should be propped up by a framework of identified confounds, mediators and suppression variables. Empirical theory can offer virtually infinite factors to include in the framework or ignore, so researchers need to exhibit choosiness. This might be a tough lesson for junior researchers, but it is a healthy part of progress. That some successful people (e.g. HD students, published authors) are apparently not concerned with correlational design, does not prohibit us from learning something valuable.

The importance of construct validity

The other of my objected comments is:

I find it extremely curious that, although the [constructs cited] are theoretically supposed to reflect dysfunctional cognitive/behaviour patterns developed during childhood, the [corresponding questionnaire] asks respondents to rate fairly broad statements as they relate over the past year. For instance, consider the statement [“I don’t belong.”] If I indicate that this item describes me perfectly when thinking about the past year, does that reasonably imply that my childhood was traumatic or neglectful? Or, does it indicate that I feel like I have not fit in lately, possibly because of situational factors (e.g. a negative work environment)? This is a potential limitation for construct validity that is worth discussing, yet you do not mention it in your work.

Construct validity, in basic terms, is the degree to which a test measures what it is supposed to. Construct validity is super important in psychological research; some would theorise it is the most important form of validity. The classic example of its importance is IQ: What does it actually measure? Researchers try to show that IQ does indeed measure a person’s intelligence (what ever that word means!), and not just a person’s effectiveness (speed, accuracy, etc.) doing a particular IQ test. It is important to understand that a low IQ score could reflect a theoretically intelligent person’s inability to give a hoot on test day.

Tests designed to measure intelligence without considering alternative constructs, like giving a hoot, can be said to have suboptimal construct validity. This is the same type of problem that my second objected comment is concerned with. Your level of agreement with the statement “I don’t belong”, as it describes your experience in the past year, could signal any number of underlying constructs. Yes, it might indicate that you had a traumatic upbringing; alternatively perhaps, in the past year, you just felt like you did not fit in.

In conclusion, construct validity is important, even if it has not been bothered with in HD students’ work or in the peer-reviewed literature. Again, while I sympathise that it might be difficult for a student to see that their study has low construct validity, it is ultimately a valuable lesson to understand why. The supervisor’s objection asked “Do we really expect students to offer any substantial critique and deconstructions of the validity of a widely utilised and accepted measure of a widely adopted clinical construct?” My feeling is that, yes, supervisors, markers, and especially students should expect to develop strong critical thinking. Just because there are published examples of something, does not imply that those examples are necessarily without flaw.

Fighting the good fight: Progress vs. success

I encourage any student to ask for more information or object to a mark if they do not understand why they got it (or feel that they have been treated unfairly). The onus is on the marker to make their criticisms clear; the student should not have to work hard to understand how a particular criticism relates to a particular criterion. That said, the onus is on students, as authors of their work, to raise and defend any concerns they might have. Besides, there is a very good reason that supervisors should not object on behalf of their students – dual interest.

The seemingly personal nature of the aforementioned objection is strange, because of the anonymous marking procedure. This has me pondering about the supervisor’s investment in the student’s thesis. In hindsight, the supervisor’s objection is littered with clues regarding the underlying motivation for their crusade. For instance, I felt it was a little odd that the supervisor mused about “…aiming for students to produce pieces of work suitable for submission to a peer reviewed journal…”. Furthermore, the supervisor explained, there is a “multitude of articles which measure and discuss [the construct cited] without offering any such discussion of construct validity.”

After a small, private investigation, I am compelled to believe that the supervisor is a highly successful author cited in the thesis. If I am correct, it is plausible that the supervisor was hoping for the student to produce a piece of work suitable for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. My comment about construct validity refers to a construct that the supervisor has published on, and so it seems I have ruffled some feathers. In light of all this, it is reasonable to expect that the need to succeed – to continue publishing – is at least part of the supervisor’s motivation for objection, yet this remains my speculation.

By the way, speaking of ‘fighting the good fight’; my friend and fellow researcher Ally is raising money for suicide prevention and mental health. She will be representing the Black Dog Institute as a fighter in the Corporate Fighter boxing match, 6 April 2018 – good onya Ally!

Conclusion and recommendation

Research-relevant concepts like correlational design or construct validity should not be taken for granted. Researchers of all experience levels must assess potentially competing motivations, particularly if they are in the dual role of researcher and supervisor (like myself). The will to succeed – to have your work published and recognised widely – is sometimes at odds with the will to progress – to learn, through critical inquiry and the brutal cycle of trial, error, feedback. In my ideal academic world, we concern ourselves with the development of sound ideas first, before concerning ourselves with their status as curriculum vitarum.

Going forward, I shall leave you with an idea proposed by Luthar (2017). Her idea can be seen as an indirect reply to Chopper’s cynical remark that began this essay.

…It might be helpful for department heads to have open, regular conversations with faculty and students about what is prioritised in their departments. For faculty who are inclined to take the chance and push students’ boundaries, they need to know whether they will be commended for truly changing the lives of some students while ruffling the feathers of others or whether they should “play it safer” in their teaching.

Excellent work !!!… I skipped read through it, but asa I’ve got a “relax” moment… Bravissimo!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting tension between progress and success – if only the two were synonymous! I think most PhD level science students I’ve met have encountered the same dilemma, and they have all unanimously become disillusioned with science as a result.

Guess there’s always good ol’ Philosophy – there’s no money in it, so no temptation to corrupt your findings!

LikeLike

I think contemporary scientists and science students should invest more time in studying philosophy. Instead, my experience of science curricula either ignores philosophy, or sort of puts it down as ‘art’. It may be art, but I feel there is an art to good science. There is no scientist without data, but what good is the scientist who cannot argue logically the meaning versus meaninglessness of the data?

LikeLike